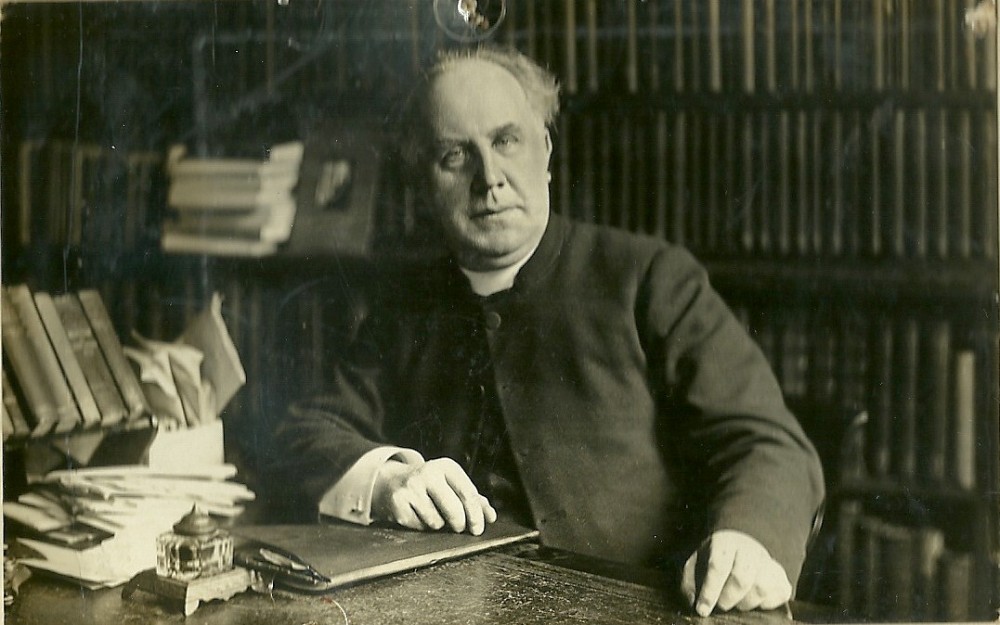

Dinsdale T. Young (1861- 1938)

Dinsdale T Young was born at Corbridge-on-Tyne, a few miles from Hexham[1], Yorkshire on November 20th in 1861, and the son of William Young, a doctor. He had a happy Christian home and this led to a secure and happy childhood. When he was 8 the family moved to Malton in Yorkshire. All throughout his life Young never quite lost the trace of his Yorkshire accent, and he was not concerned about it. Young was always very close to and got a great deal from his father[2], who had his practice in the town. Later he described how his father gave him a copy of Andrew Bonar’s Life of Robert Murray McCheyne, “I should scarcely exaggerate did I describe him as my earliest religious teacher. He was my father’s devotional companion. My present copy of his life and works was given me by my father in my boyhood. It is scored from cover to cover, and I have read it times beyond numbering: in fact, I am constantly referring to it. My first visit to Dundee was expressly to see McCheyne’s church and to stand by his grave ... I prize McCheyne and his teachings beyond compare. I am always quoting him to my people. I have frequently lectured on him in various parts of the country. Very near to my Bible stands McCheyne, whose ways in Christ have been such guiding lights to my life”.[3]

Young became a Wesleyan local preacher at 16, after taking his first public service at 15. “It seemed to have been for ever settled in heaven that I was to be a preacher. From my earliest childhood, I regarded it as my destiny. So, my father, and mother, and all who knew me, seemed to regard it … certainly I never had any other idea. … I preached and conducted services in my nursery, preached in various rooms of the house in dawning boyhood, preached in the houses of relatives and friends; dreamed of preaching – and all this was surely prophetic of, and preparatory for, a life of preaching.”[4] He came to have quite a career as a juvenile preacher and lecturer and in 1879 the Wesleyan Methodist Conference Young as a candidate for the ministry. At the same time he went to Gateshead, Durham, where he spent 9 months with the Bensham Road Chapel circuit. In 1880, Young began his three years of training at Headingley College in Leeds.

On graduating, he joined the Highgate circuit in London, where his own personal charge was Hornsey Chapel. In 1886, he married Emma[5], the daughter of Alderman Hindmarch, a Justice of the Peace in Gateshead. Then in 1887, he moved to Birmingham and joined the Edgbaston circuit. Three years later, he was on the move again, and to York and the Centenary Wesleyan Chapel. It was at this time that he was approached by the leaders at Westminster Chapel, London, but Young declined an extended call to minister there.

During the 90s Young was frequently on the move; there was Gravel Lane Chapel, Salford near Manchester, where he spent 5 years, then Denbigh Road Chapel, Bayswater, London, and then to Nicholson Square Church in Edinburgh. Soon he returned to London and initially ministered for 2 years at Great Queens Street, which became Kingsway Hall in Holborn, before taking up a longer residence at Wesley’s Chapel in the City Road (1906-1914).

The year 1914 was significant for Young; not only was he President of the Wesleyan Conference for the year, but he also moved to his final charge at the Central Hall, Westminster, where he ministered for his last 23 years. Methodist Central Hall Westminster was opened in 1912 as a monument to mark the centenary of John Wesley's death (the founder of Methodism). The site was formerly occupied by the Royal Aquarium (primarily a music hall), which was purchased by money raised through a huge Methodist fund raising venture. The 'Wesleyan Methodist Twentieth Century Fund' (or the 'Million Guinea Fund' as it came to be known) opened in 1898 with the aim of raising a million guineas from a million Methodists to help facilitate a great push forward of Methodism. Interestingly the early meeting for the Fund were at Wesley’s Chapel, and so Young would have been aware of the project. This fund closed in 1904 with just over a million guineas, a quarter of which was allocated to the design and construction of this centenary building. The remaining funds were invested in new Chapels, foreign and home missions, education, soldier's and sailor's homes, temperance work and children's homes.

The design for this 'monumental building of Methodism' was chosen from 132 entries in an anonymous architectural competition. The rules of the competition stated that the design had to be non-Gothic and the general philosophy of the Methodist movement was that buildings were not to resemble churches. The intention was to create non-intimidating but welcoming buildings so that people who had no connections with the Christian church would feel comfortable and able to enter them. “The raising of the fund had been in the able hands of the Rev Hugh Price Hughes and Sir (then Mr) Robert Perks. Hughes died before the hall was completed and so had no part in the discussion as to the method of using it. In the Conference Dr Young had always been an outstanding man who had advocated the ordinary traditional Circuit life of the Wesleyans as against this new-fangled idea of large Central Halls with their social implications. He had not opposed those implications, but had felt that there was a real danger of general failure amongst the ordinary churches if too much attention was given to financing, and helping by personnel, the more favoured aggressive work of the Mission Halls. … After a year or two of limited success by less popular preachers at Westminster Hall, some genius – Sir Robert Perks is generally considered to have been the man responsible for the idea – thought of Dinsdale Young.”[6]

Crowds went to hear him preach at the Central Hall, where he reigned as a prince of the pulpit for many years. He presented himself well wearing a frock coat and silk hat as he moved among the people in the communities. Loved and respected for his Bible ministry and natural warm personality. Long white flowing hair gave the appearance a conductor of an orchestra. He was a minister of the old school, in his theology and preaching, and he gloried in the title. When some people hinted at his narrowness, he was ready to quickly reply that he could claim to have studied both sides more thoroughly than those who were supposed to be modern. (What changes?)

Dr Young was a minister in Edinburgh in the time of Alexander Whyte and Henry Drummond, who were great magnets to many, but Dinsdale Young held his own and his congregations were unaffected. When he came to the Central Hall, Westminster, where he preached for twenty-five years, not only was it to the largest congregations in London, but also to the largest in Britain. A glorious voice wonderfully used, it was an organ voice, and it was said he could have electrified a congregation just by his sounding forth of the word "Mesopotamia" he was masterly in the art of words. Having felt led of the Lord on some passage or text of Scripture, he then referred to his best commentaries to be found on his well-lined library shelves. He loved to quote frequently from Bible, commentary and biography. (Some would say too often regarding the last two)

”’Preaching as an ordinance,’ said Dr Young, ‘is part of 'God's good pleasure.’ There has been no revocation of this supreme ordinance. It is the Sacrament. Of all the acts of worship it is the most helpful. The churches grieve God's Spirit when they ignore or depreciate preaching. But he made every part of the service effective. He would say, ‘Let us now worship as we sing,’ and then read out the first verse in such a way as to make sure a familiar hymn shed some new glory.”[7] ”Fundamentalist as he undoubtedly was, Dinsdale Young did not bother crossing swords with Modernists, and the many who disagreed with his views were always to be found enjoying his preaching. He did not argue, he proclaimed. He was not an apologist, but a herald. He knew no hesitancies or wistful doubts, but preached with all his soul a gospel of grace abounding to the chief of sinners. What a thrill it was to hear him quote as his own personal experience, William Cowper's lines:

‘E'er since by faith I saw the stream

Thy flowing wounds supply,

Redeeming love has been my theme,

and shall be till I die.’”[8]

“He was a minister of the old school in his theology and preaching, and he gloried in the title. And when some people hinted at his narrowness, he was ready to reply that he could claim to have studied both sides more thoroughly than those who were supposed to be modern. And a minister of the old school as he was did not fail to attract young people. His popularity was phenomenal. Wherever he went, and he was constantly travelling all over the country, crowds flocked to hear him.”[9]

The great preacher's faith did not fail him at the last. His last distinguishable words on January 21st 1938 were, “I triumph”. It was the same triumphant note that always seemed to characterise his preaching. ‘Lord make all Your preachers today 'Young' at heart and in the pulpits of our country.’

The Man:

Young was a man of remarkable talents and of attractive personality. He put on no false airs, was natural, unassuming and very kind in every way. Always displayed a delightful sense of humour, and was good to be with.

Young attracted young and old alike by his preaching. Wherever he went, and he was constantly travelling up and down the country, crowds flocked to hear him. “He put on no airs: he was natural, unassuming and kindly to a degree; and his conversation so rich in reminiscence and anecdote was always a delight. He could be playful and humorous to a degree. There was nothing ethereal about Dinsdale Young. He had a sweet tooth, especially for chocolates. He loved a good cigar, and could smoke almost any kind of pipe – being like Spurgeon in saying he enjoyed these to ‘the glory of God.’ But he declined smoking on the street.”[10] “Dr Young had his little likes and dislikes...One day I was sitting at tea with him and teased him about being fond of chocolates. He admitted at once that he was, and I think headed, ‘fancy cakes too’. I have been wondering whether I ought to say that he indulged in the fragrant weed, as some are sensitive about that. All I need say is that in that matter he never set a bad example to others. He never smoked excessively...So few people ever saw him smoking that many will hardly believe that he indulged in that way at all. He cared very little indeed for the pleasures of the world, for sports and so on. I don’t suppose he knew anything about theatrical shows or about film stars. He may have been to a cinema, but I doubt it. He was moderate and abstemious in all things, and never lost his natural dignity. His serenity was captivating...When asked what his recreations were he replied, ‘Walking and reading.’[11]

Young had an extraordinary voice and he used it to the full to proclaim the glorious Gospel of Christ. “It was an organ voice, and it was said that, by his remarkable control of it, he could have electrified a congregation just by his sounding forth of the word ‘Mesopotamia’. There was something rich, full, and resonant in its tones.”[12] “What a resonant voice he had! How perfectly phrased were those sentences of denunciation! How well modulated his speech! He exhibited all the arts of the practised preacher and speaker, and had the supreme quality of concealing the art. In fact he was such an artist that use had made the art into a second nature.”[13]

“Dinsdale Young never used notes, so he had no temptation to speak into his book board. He had a power of ready speech. He had prepared his sermon so that one part fitted naturally on to another. He spoke out and spoke up. He had learned the art of breathing his words out exactly as a skilful soloist does. He was never dull. One might disagree with him, as many people in his huge audiences did, but nobody ever went to sleep when he spoke or preached.”[14]

In Dr. Dinsdale T. Young[15] W.R. Nicoll[16] recognised a powerful preacher[17] from a similar mould to Spurgeon. Nicoll encouraged Young to publish volumes of his addresses and also to write articles for the British Weekly. Invariably such articles[18] described the Wesleyan Conferences[19] or other subjects, such as his summer holidays. Young, in turn, was most appreciative of Nicoll’s service to the Church as editor of the British Weekly: “Many a time I have seen a suggestive text, say, in the British Weekly, of a given Thursday, and I have preached upon it the next Sunday on absolutely different lines.”[20] Also, “Though I have been compelled in these pages to refrain from mentioning living men, yet gratitude of no ordinary quality compels me to add in this department of literature two names: Dr. Alexander Whyte, and Sir W. Robertson Nicoll. Their allusions to preaching have always stimulated me in high degree.”[21]

Young brought his own assessment after Nicoll’s death: “A great pillar of the Church has fallen. Its massiveness and its beauty have alike rejoiced me for many long years … many will attest his literary genius, his political influence, [and] his wonderful editorial faculty. I would the rather acclaim his splendid loyalty to the evangelical faith. How grandly true he ever was to the supreme doctrine of Christianity – the Atoning Sacrifice! … I know that he was very solicitous concerning the preaching of the Gospel of the Atonement in the churches … Closely associated with this was his deep delight in C H Spurgeon. Sir William once told me that it was his custom to read one of Spurgeon’s sermons every evening. In those wonderful discourses, he found the replenishment of his soul. He had a delightful enthusiasm for preaching. I never read a pronouncement of his on that subject that did not find a response in my judgment and did not rekindle my ardour for that ‘royal ordinance’ … What a fascinating literary style God had blessed him! My heart sinks when I think of that deft and delightful pen being laid down forever … Sir W Robertson Nicoll has been a fountain of inspiration to preachers. They have had no such literary friend these forty years. To what splendid teachers he has introduced us! I should be forever his grateful debtor if only because by him I first came under the spell of Dr Alexander Whyte … I ventured on one occasion to say to Sir William that I thought his greatest discovery, amid his many great discoveries, was Dr Denney. He instantly replied, ‘I believe you are right’.”[22]

[Note: Biographer – Harold Murray: Dinsdale Young; the Preacher, N/D]

Books – published by Hodder & Stoughton – unless shown:

Girding on the Armour (1894)

Unfamiliar Texts (1899)

Neglected People of the Bible (1901)

The Crimson Book (Evangelical sermons)

Peter MacKenzie, as I knew him

The Gospel of the Left Hand: A Book of Evangelical Cheer (1909)

The Enthusiasm of God

Messages for Home and Life (1907)

The Travails of the Heart [Epworth Press]

Silver Chains: Meditations: Devotional and Expository [Silver Wedding Dedication, August 1911]

The Unveiled Evangel [‘Preacher of Today Series’: Epworth Press]

Heroic Leaders: ‘Great Saints of British Christianity’

Robert Newton: An Eloquent Divine

Richard Roberts: a Memoir

Stars of my Retrospect: Frank Chapters of Autobiography (1920)

Popular Preaching (July 1929) [Epworth Press]

A study of Dinsdale Young

Like Joseph Parker, Dinsdale T. Young was a Northumbrian, having been born in 1861 at Corbridge-on-Tyne, where his father was a physician.

In early life he decided to become a Methodist preacher and began to preach at the age of fifteen. He attended Headingley College, Leeds. He was ordained in 1879 and was the youngest person till then to be ordained a Methodist preacher.

After twenty-seven years of "travelling," as Methodists call it, in large city circuits he came to an anchorage in London. In 1906 he became minister of Wesley's Chapel, and within a very short time he had become a fixed star for Methodists. The historic chapel soon became crowded.

Something was lost, in point of picturesque fitness, when he was transferred to the Central Hall, Westminster. There was a certain incongruity between the modern Mission Hall -- with its tip-up seats and its concert-room decorations -- and the stately head and ambassadorial bearing of the frock-coated preacher.

The great congregations that came in undiminished numbers to the Central Hall proved baffling to the liberals who declared repeatedly that Young would soon preach to empty seats because of his fundamentalism. Young was a superb orator and a defender of evangelical doctrine. However, he never attacked his opponents. He was content to set forth the teachings of God's Word in a positive way and pay no heed to his critics. He often preached or lectured seven or eight times in a single week and travelled an average ten thousand miles a year to keep his preaching engagements. During some years of his ministry he had a highly distinguished neighbour in Dr. Jowett at Westminster Chapel, who was a far more celebrated man than Young and by far his superior in intellect and pulpit quality. Yet it was a familiar saying that "Jowett gets Dinsdale Young's overflow."

Jowett once asked an office-bearer why so many people arrived twenty minutes late and were distributed through such vacant seats as were left. He was rather shocked to be told that they had come away from the Central Hall, unable to get a seat.

Young was a man of remarkable gifts and attractive personality. He was natural, unassuming and kindly to a degree. He always moved with a certain grandeur and was never seen without his frock coat and silk hat. He grew old picturesquely, his white locks streaming out behind him as though he were Liszt, while two triangles of white hair flanked the high pink dome of his forehead. He preached for twenty-four years at the Central Hall, not only to the largest congregation in London, but to the largest in Britain. A glorious voice, wonderfully used, was one of his great gifts. It was an organ voice, rich, full and resonant in tone.

Having chosen his text, he went straight to the best commentaries he could find on his well-filled library shelves. He often mentioned his delight in Calvin, Matthew Henry, Adam Clarke, and, above all, Thomas Goodwin. He frequently consulted the writings of Spurgeon, Newman, Dean Vaughan and Alexander Maclaren. He is said to have preached on over seven hundred texts at Wesley's Chapel and some thousands of texts at Westminster. He clung to the principle of having three divisions, saying that Maclaren's "three-pronged fork" was a useful instrument.

Young is described in that lovely book of George Herbert, "A Priest of the Temple," where he says, "the Country Parson preaches constantly, the pulpit is his joy and his throne. When he preaches he preserves attention by every possible art."

Young himself said "Preaching as an ordinance is part of God's good pleasure. There has been no revocation of this supreme ordinance. It is the sacrament. Of all the acts of worship it is the most helpful. The Churches grieve God's Spirit when they depreciate preaching." Young did not argue; he proclaimed. He was not an apologist but a herald. He knew no hesitancies or wistful doubts but preached with all his soul a gospel of grace abounding to the chief of sinners. What a thrill it was to hear him quote, as his own experience, William Cowper's lines:

E'er since by faith I saw the stream

Thy flowing wounds supply,

Redeeming love has been my theme

And shall be till I die.

His faith did not fail him at the last. During moments of consciousness, as he lay awaiting the final call, he continually repeated lines of the hymn, "Just as I am," and his last distinguishable words were, "I triumph."

What was the secret of his popularity as a preacher? In 1929 he delivered the Fernley Lecture at the Wesleyan Methodist Conference on "Popular Preaching." Popular preaching, he said, must aim at the many, not at the cultured few. It must be expository Bible preaching. It must be evangelistic. No preaching is abidingly popular which is not aflame with redeeming love. It is "the satisfactory Cross" which makes preaching popular. The only way to build up church attendance is to preach Christ crucified.

"Preaching which has taken the deity out of Christ, the Atonement out of the Cross, faith out of the method of salvation and the indwelling of the Divine Spirit out of Christian experience 'is cut down like the grass and withers'."

Young was a firm believer in the preaching of both Law and Gospel.

"No preacher," he said, "is permanently popular if he does not make people uncomfortable. We must wound with the sword of the Spirit. We must show them all the mercy by showing them all the sin."

All his preaching was deeply rooted in the Bible, as can be seen from a study of his many published volumes of sermons such as Unfamiliar Texts, Neglected People of the Bible, The Unveiled Evangel, and The Crimson Book.

He said: "Let a preacher leave his Bible and he forsakes his own mercy in every sense of the word. Not least in this that he casts himself off from the fountain of effectiveness. His own thoughts will soon pall. Anecdotes will fail to interest. The gossip of the hour will perish with the hour. But if he cleaves to the Bible he will have a word which will attract and help."

Some one asked Joseph Parker if he thought that literature would ever supersede preaching, and his reply was, "Not till correspondence supersedes conversation." Like Parker, Young believed that nothing can ever eclipse or rival preaching. He had the great gift of unction. He often chose words deliberately for their sonorous qualities. It was an experience to hear him recall some memory of C. H. Spurgeon, "that royal preacher." He once gave a lecture on "An Old Album Reopened," in which he spoke of his personal memories of Spurgeon, Parker, Peter Mackenzie and other famous preachers. With what gusto he quoted from William Law and John Bunyan and John Wesley! He would roll their very names around his tongue; to experience this the recommended reading would be his autobiography, Stars of Retrospect.

Dinsdale Young's sermons were unashamedly simple, though expressed in beautiful English and delivered with dignity and seriousness. He declared that he had never forgotten what an old saint once said to him: "I often see directions given to preachers, but I never see them recommended to pray more that they may preach better." He believed that the preacher's private prayer before preaching would work wonders during the service. The chief element in his appeal was his absolute certainty and confidence in delivering the old Gospel. He delighted in dwelling on "the tender grace of a day that is dead." He loved to use the old phrases, the language of Canaan, and would always evoke "Amens" and "Hallelujahs" from the old people in the congregation. He had an avowed preference for the old ways and the old terms. He was a champion of orthodoxy, of the old Gospel, the old Book.

J. T. Wardle Stafford, a lifelong friend in the Methodist ministry, in a tribute in The British Weekly after Young's death in 1938, wrote this:

"Of all the preachers in England who speak from the vantage ground of a great metropolitan Church and who are entitled to serious consideration by reason of their manifestly attractive power, Dinsdale Young is the only one who can be called without any qualification whatever, an old-fashioned, foursquare, evangelical preacher of sin and salvation."

"He is so orthodox that he has become heretical. His presence, his manner, his voice, his command of mellifluous English, his consistent and uncompromising adherence to the fundamentals of the Christian faith, secured for him the attention and goodwill of all who heard him."

[1] “My birthplace was Corbridge-on-Tyne, a beautiful village, now a summer resort. It is but a few miles from Hexham – the place of Dr Joseph Parker.” Young, Dinsdale T: Stars of Retrospect (Hodder & Stoughton, London 1920) 2

[2] “I have written and spoken much of my Father. For twenty-two years he resided at Malton, where he died in 1891 at but sixty years of age. Never were Father and son more entirely one that were he and I – his only child. Ours, I deliberately say, was an ideal relationship. He was as a tender elder brother to me, as well as the most judicious of fathers. I steadily regard my Father as the finest Christian I ever knew.” Young, D T: Stars, ibid 3

[3] Ibid 184

[4] Ibid 26

[5] Emma Hindmarch died in 1936 and the family consisted of four children: William Dinsdale [Became an Evangelical clergyman in the Church of England], George Edward [Became an officer in the Indian army], Alan Dinsdale [Entered business life] and Muriel Dinsdale, who remained a helper at home [died 1920?].

[6] Rattenbury, Owen: ‘Dinsdale T Young – The Popular Preacher’, Little Library of Biography, No 73 (RTS – Lutterworth Press, London N/D) 8-9.

[7] Gammie, Alexander: Preachers I Have Heard (Pickering & Inglis Ltd, London, N/D [c1945]) 147

[8] Gammie, Alexander: ibid 147

[9] Gammie, Alexander: ibid 145

[10] Gammie, Alexander: ibid 145

[11] Murray, Harold: Dinsdale Young; the Preacher (London, Marshall, Morgan and Scott, N?D) 47-8

[12] Gammie, Alexander: op cit 146

[13] Rattenbury, Owen: ‘Dinsdale T. Young – The Popular Preacher’, Little Library of Biography, No 73 (RTS – Lutterworth Press, London N/D) 4

[14] Rattenbury, Owen: ibid 5

[15] Dinsdale T Young (1861-1938) Methodist Preacher and having trained at Headingly College, Leeds [1882], held successful pastorates in Birmingham, York, Manchester, Edinburgh, but it was in London that he made his mark, at Queens Street, Holborn [1904], Wesley’s Chapel, City Road [1906-1914] and Westminster Central Hall [1914, remaining there for 23 years].

[16] Nicoll, William Robertson: 1851-1923, Editor of the British Weekly: see Ives, Keith A.: Voice of Nonconformity, (Cambridge, Lutterworth Press, 2011) 150

[17] Here there was a Scottish connection, for Young spent three years at Nicolson Square Church, Edinburgh: “I was favoured with a romance of manifold prosperity. Immediately the church filled to overflowing alike on Sabbath mornings and evenings. So it remained during my ministry there. I, on several occasions, had the remarkable experience of having more people excluded than could be crowded into the building … when I closed my ministry in Edinburgh the Lord Provost (Sir Robert Cranston) presided at a dinner with which I was farewelled. The Synod Hall was taken for my last two Sunday evening services and was densely crowded.” Young, Dinsdale T: Stars of Retrospect (Hodder & Stoughton, London 1920) 64

[18] “Another very happy literary pursuit of mine has been the writing of sketchy articles concerning my summer holidays, and other subjects. Many of these have appeared in the British Weekly, The Methodist Times, and other papers. I have been simply amazed, and that not seldom, at the gratitude of readers has often almost drawn my tears. From distant lands I have received messages of thanks, especially for sketches in the British Weekly.” Ibid 165

[19] “For several years I wrote, in, a series of sketches of the Wesleyan Conference. It involved early rising and late sitting up during the sessions of the Conference, but my friends who read the sketches abundantly rewarded me by their warm appreciation.” Ibid 166

[20] Ibid 118

[21] Ibid 180

[22] Young, Dinsdale T: ‘Personal Tribute’, British Weekly, May 10 1923