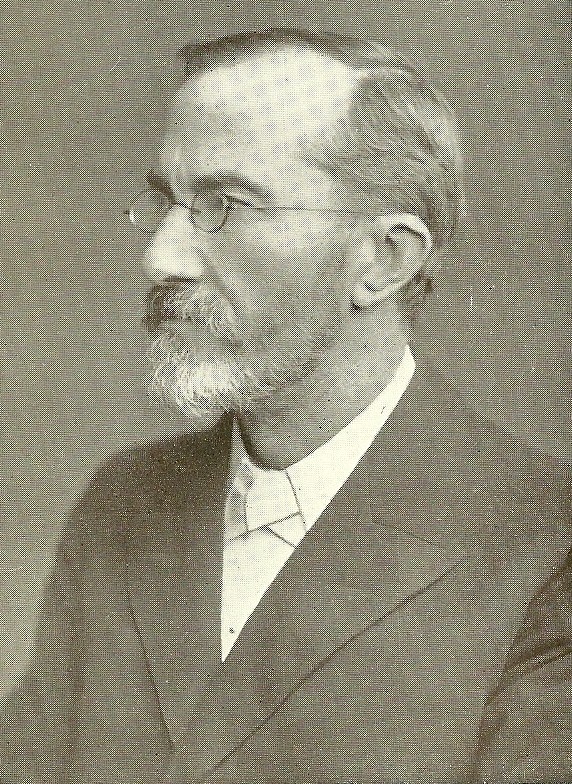

James Denney –a spokesman for the ‘Believing Critics’ and their attitude to Scripture

|

|

Paternoster has produced an excellent series for those seriously interested in Church History and Historical Theology – ‘Studies in Evangelical History and Thought.’ One of the more recent studies is James Denney (1856-1917) – An Intellectual and Contextual Biography, by James M Gordon[1]. The author has not only given us a well-crafted book that is pleasurable to read, but, also, has written empathetically about his subject so that Denney emerges from Gordon’s thorough contextual and biographical approach. This study enables the reader to qualitatively appreciate Denney in his very individual life and the emphases and concerns of his times. Put simply this book is too good a read to be missed.

The Study was the research that gained the author’s PhD, and his interest in the theology and thought of Denney had one of those enviable breaks, when he found that New College, Edinburgh, housed “a large collection of Denney’s unpublished papers [that] had been deposited … and that they as yet were unexplored.” Gordon seeks to place these papers into a biographical outline of Denney’s life and times, and this is the best and most useful context in seeking to appreciate the progression of Denney’s thought. It seems that in the main the collection consists of sermon notes from Denney’s ministry, mainly while at Broughty Ferry Free Church (1883-1897), and Denney’s lecture notes, when he was at the Free Church Theological College in Glasgow (1897-1917). Gordon also includes other unpublished materials, such as some letters of Denney found in the papers of Sir William Robertson Nicoll at King’s College, Aberdeen, and were not included in the volumes of Denney’s letters published by Nicoll and James Moffatt[2].

Gordon’s main concern is to engage with these unpublished papers, and scholarship and ordinary readers will be grateful for the painstaking and thoughtful results that have come from his studies. Gordon does engage with previous writers who have looked at the work of Denney, particularly John Taylor’s study God Loves Like That![3] However, his main concern is to engage his readers with the unpublished papers and share the insights and progression of Denney’s thinking that he finds indicated there.

James Denney is one of those theologians who replays abundantly close study because of his emphasis on strengthening the Church and enabling and equipping believers to be confident, equipped and appreciative of their essential relationship with their Saviour – The Lord Jesus Christ. But Denney can be difficult, for some Evangelicals, because he takes an unashamed left (liberal) Evangelical wing on some issues, not least, the Doctrine of Scripture. Also there is Denney’s forthright style that many simply called ‘combative’. Gordon comments: “Denney did not court controversy, but neither did he avoid the consequences of plain spoken loyalty to the truth as he perceived it.”[4] Denney referred to himself, in writing to his friend, W Robertson Nicoll, “Perhaps I have what Lord Morley calls the intellectual fault of pugnacity.”[5] Gordon seems able to capture the driving motivation of Denney, and so, whether we agree with Denney’s assessment or not, we have to acknowledge the integrity and rigour with which Denney argued his corner. Gordon puts it, “To Denney’s mind, loyalty to truth was a moral and intellectual imperative, taking precedence over all other demands placed on the conscience of the Church’s theologians. Orthodoxy was not found in creedal fixity, or determined adherence to past articulations of the Faith. These had served the Church well, but the comfort they gave could only be maintained at the cost of fading relevance and loss of intellectual credibility … Insisting on the absolute centrality of Christ as portrayed in the New Testament record of apostolic experience and testimony, Denney placed historically founded and experientially verified knowledge of Christ above all other confessions or articulations of Faith. Insisting also on the nature of Scripture as fallible text bearing infallible witness to the One whose reality and authority is final for every Christian conscience, Denney inevitably drew criticism and sparked controversy with those less certain of their theological bearings.”[6] Whatever else, Denney is always a challenging, thought provoking read, and if you disagree with him, the reader is pushed to be sure he knows why he has the temerity to think differently from the professor.

There are a number of themes in Denney’s theology that Gordon brings out and examines. One of the main concerns was Denney’s role as the ‘spokesman’ for the ‘Believing Critics’ in their attitude to the Scriptures, which seems to interlace Gordon’s study, even as it interlaced Denney’s role as a theological educator. The term ‘Believing Critics’ is viewed as a historical phenomenon, for, there is a sense that all Evangelicals who are involved in any preaching and teaching capacity, are critics or interrogators of the text of Scripture, while, of course, emphasising the need to believe, and trust in the Word of the Lord from that passage. Historically N M de S Cameron defines ‘Believing Criticism’ as “the acceptance of biblical ‘higher criticism’ by pious scholars in Scotland in the later nineteenth century.”[7] This group emerged as a middle position between the rationalistic or ‘unbelieving’ criticism associated with Continental University theology [particularly from Germany] in the Nineteenth century. “This was a crucial development in the dissemination of the critical approach to Scripture within the conservative piety of nineteenth-century Scotland, and especially within the Free Church. Indeed, it was in the Free Church that it made most progress, since that was where the leading [‘Believing] Critics’ were to be found.”[8]

It is generally agreed that A B Davidson was the originator of the phenomenon of ‘Believing Criticism’, and his motivation was to seek to give his abler students, at New College, Edinburgh, something to use and satisfy their minds with, something more demanding than the merely reciting the ‘mind numbing’ orthodox theology, which was seen as the staple diet in the College of his day.[9] Davidson was able to hold orthodox Evangelical conservatism in doctrinal piety, while at the same time reading and exploring new radical challenges to orthodox biblical traditions. Davidson was cautious and genuinely slow to commit himself publicly. He had a sincere and high regard for the Evangelical Fathers of the Kirk, who were being disturbed by the implications of the newer evaluations. However, his students did not have the same reticence, and William Robertson Smith seemed to decide to go on a personal crusade to gain recognition for the new views of the Higher Critics. Davidson remained silent during the trial period of Smith (1875-1881), and it was only in the changed atmosphere, towards the end of his life that he was definite in his affirmation of many of the conclusions of the Higher Critics. Sadly his successors found it hard to hold to Davidson’s line and became more advanced liberal critics than Evangelical believers.

It must be appreciated that Denney and his colleagues moved in an atmosphere of hostility and extraordinary vituperative verbal warfare. The truth is that neither the Orthodox Conservatives nor the Liberal Radicals, which included varying strengths of Believing Critics, covered themselves with honour in the severity and savagery with which they depicted each other. There was ‘politicising’, ‘polarisation’, party spirit – factionalism, in the failure to appreciate the ‘enemy’s mindset. Fundamentally both sides seemed to pay only ‘lip service’ to the sincerity and honesty of the ‘enemy’; rather, both sides threw the charge of ‘a lack of integrity’ into the face of the other. It seemed that both sides seemed to see truth territorially and were determined that their position was the blueprint for the future direction of the Church. Little wonder that, in all probability, the manner of the debate possibly caused as many casualties from the Christian Faith as did the content of the debate!

From his college days [1879-1883], Denney identified with Robertson Smith and the ‘Believing Critics’: “Denney’s theological education took place during the climax and immediate aftermath of the affair and at the hands of some of Robertson Smith’s most vocal and loyal supporters. It is this ethos of supportive, even combative sympathy with Smith, which was highly significant in the formation of Denney’s views on the nature and authority of Scripture, and its relation to criticism.”[10]

It needs to be remembered, also, that there were two areas of separate concern, they overlapped and often became confused, but they are distinct: Firstly, there were those who simply wanted the academic freedom to be able to examine in detail the new and the latest materials, evidence, opinions that scholarship was propounding in the field of Biblical and theological studies. They believed that to do their job as college professors and lecturers, they should keep their students ‘up to speed’ with such developments as were taking place. Then, secondly there were those who simply wanted to modify the ‘traditional’ views on the History and Inspiration of the Scriptures, if it was felt that scholars were establishing a more credible and tenable position, in the light of modern thinking. There were many, in the early days, particularly amongst the believing critics, who felt that this position could be held and at the same time they believed that they could still regard and hold that the Scriptures were God’s Word and the deposit of God’s infallible truth for His Church and Mankind.

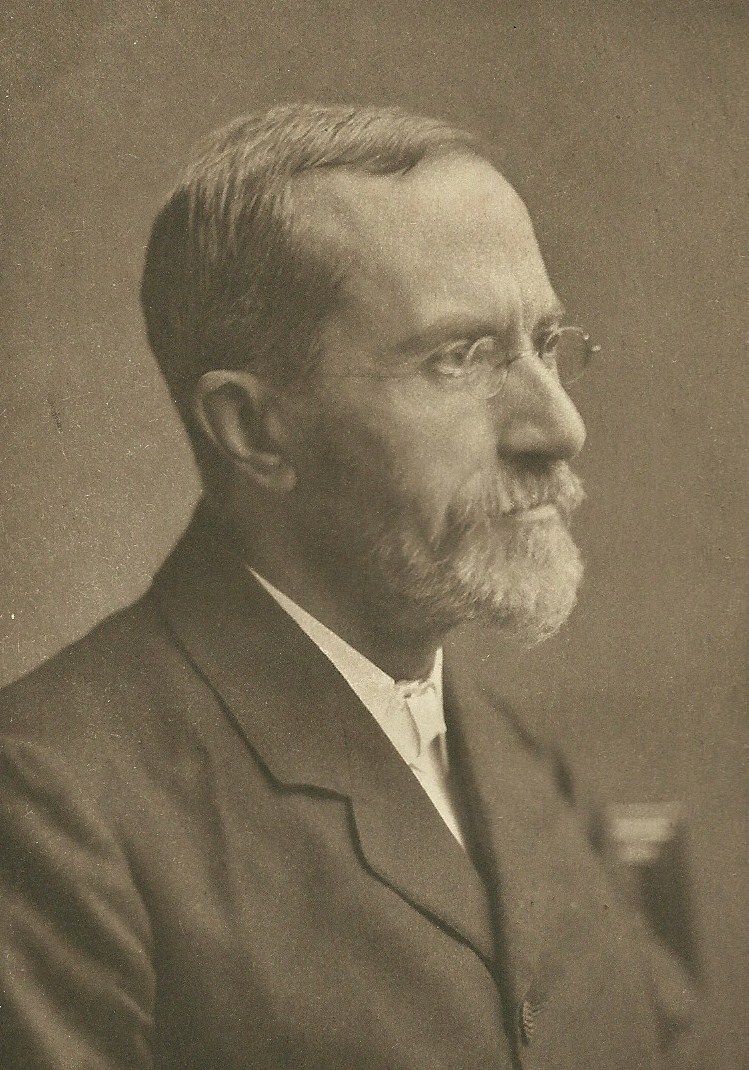

The second position would identify William Robertson Smith, who was not satisfied with the first position and had determined in his mind the Church should move on. Smith confused the issues in many people’s minds by going for broke in his personal crusade against the ‘old, untenable and inadequate’ views of his opponents. Many of his supporters were only concerned with the first position and concerned about academic integrity and freedom, well, at least at the beginning of the controversy. Here were many of Denney’s tutors, some of who were later to become his colleagues; figures such as, James S Candlish, T H Lindsay, and A B Bruce, could be among those identified. Principal Rainy and Marcus Dods at New College, Edinburgh, as well as others swelled the ranks of ‘Believing Critics’. These leaders were backed up by the journalistic endeavours of W Robertson Nicoll with the Expositor for ministers and the British Weekly at the more popular level. Denney was to make significant contributions to both these journals. Also the copious work of James Hastings with his regiment of Encyclopaedias, sought to popularise and spread confidence for ‘the assured results of Higher Criticism’.

Denney’s intervention in an Assembly debate in 1891 made him suspect to his conservative minded colleagues. Gordon quotes a fuller version, rather than the usual abbreviated segment, which more honestly shows Denney’s concern: “The infallibility of the Scriptures was not a mere verbal inerrancy, a historical accuracy, but an infallibility of power to save. The Word of God infallibly carried God’s power to save men’s souls. If a man submitted his heart and mind to the Spirit of God speaking in it, he would infallibly become a new creature in Christ Jesus. That was the only infallibility he believed in. For mere verbal inerrancy he cared not one straw. It was worth nothing to him; it would be worth nothing if it were there, and it is not … he did not think anybody has a right to accuse them or to suspect them in the very faintest degree of falling away into rationalism, or denying the Divine Authority of the Word of God. Authority was not authorship”.[11] To which Gordon comments, “The level of unguarded frankness in a young minister betrays strong feeling and Denney’s temperamental inability to discount truth in the interests of tact.”[12] Was Denney being disingenuous? In his way he was motivated by a passion to evangelise in his own day and simply wanted to get rid of attitudes and views that he considered got the way or stopped short of that personal knowledge of Christ, which Denney knew to be all important.

Gordon helpfully explains the background to Denney’s visit to lecture on Christian doctrine at the Congregational Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1894. Circumstances and events had made the Doctrine of Scripture even more of a live concern than it was back in Scotland. He was well received, but his ninth lecture excited considerable discussion and it was titled ‘Holy Scripture’. When published as Studies in Theology[13], Chapter 9 was the only one to be rewritten, “not with the view of retracting or qualifying anything, but in order, as far as possible, to obviate misconception, and secure a readier acceptance for what the writer thinks true ideas on the authority of Scripture.”[14]

Most interestingly Gordon has found the original lecture in the New College collection and helpfully interacts with the differences he observes. He writes of the revised version, “Much more than the sanitised revision, this lecture reveals Denney as logic on fire, combining in his most powerful writing, a rationally driven methodology with a passion driven motivation. The hearers of the original manuscript were left in no doubt that Denney was angered by what he took to be untrue ideas about the authority of Scripture, and inspired by what is possible in the lives of people, if with true ideas about the Bible, they are able to encounter not an infallible text, but an infallible God.”[15] Gordon notes that in his revised edition Denney even “quotes Warfield and Hodge to support his view of Scripture as primarily a means of Grace.”[16]

Here it seems that Gordon was possibly too engrossed in comparing manuscript with the printed version of the Ninth Lecture, that he misses some pertinent comments that have been published in 1925. In Darlow’s biography of Denney’s friend, Sir William Robertson Nicoll[17], there is a letter which shows that Nicoll sought to advise his friend. Nicoll wrote both in his role as friend and also as a literary adviser for Hodder and Stoughton, who eventually published Denney’s lectures: “I meant to write you a long letter before I left home about the Bible chapter … so far as it goes, I agree with it – but I think its tone is hesitating as compared with the other lectures, and it is not clear like them.”[18] Nicoll goes on to list some pointers for Denney’s consideration, and under one heading, he writes “You must also note that the only respectable defenders of verbal inspiration – the Princeton school of Green and Warfield …” and again “You see what I am driving at in these clumsy and compressed remarks. It is that you should take account of the arguments and thoughts about the Bible that are moving in average minds.”[19] Denney, at times, seemed to struggle with this last insight given by Nicoll, but then, he could never just write for ‘average minds.’ Gordon enables his portrait of Denney to remind those of us who come from the more conservative Evangelical end of the scale of attitudes to the Inspiration of the Scriptures, that it is possible for us to become static and stop at the truth of the Authority of the Bible and fail to go on to the authority of our living and loving, personal and supreme God.

‘Biblicism’ is an essential Evangelical distinctive[20], but it has to be accepted that there is a grid or scale, which stretches from those who hold a full inerrancy, infallibility of the biblical text to those who, although they respect the text of Scripture and believe that God speaks with infallible authority in to people’s lives, refuse to be bound by a rigid Doctrine of Biblical Inspiration. In other words those for whom ‘Believing Criticism’, after the historical pattern, is still a real and comfortable option.

To hold the kind of position that ‘Believing Critics’ does, requires a good and a disciplined mind. Perhaps, also, a mind that can hold theological distinctions, without these hurting that essential reality of trust of the individual’s personal ability to receive the communication of an authoritative, living ‘Word of the Lord’ from the Scriptures. Undoubtedly it can be done, James Denney exemplifies this, but in the concluding words of ‘an old war-horse’, R L Dabney, after examining the views of William Robertson Smith, cause us to reflect carefully: “Finally, while we do not presume to question the personal sincerity of Mr Smith’s protestations of his own confidence in the substance of the Bible as containing a divine religion, we warn him that few who adopt his principles of criticism will think that they can consistently stop where he stops. The Germans whom he follows do not think so. Their first principle is, that the supernatural is incredible. The very aim of their policy in adopting a method so rash is, to be able to eliminate this supernatural out of the Scriptures. And such will be the tendency wherever such methods are used.”[21]

Gordon presents us with a vivid human portrait of a skilled spiritual mountaineer. He tackles difficult climbs and dangerous ascents without some of the equipment of ideas and truths many of us consider as safe and reliable for good progress in our Christian thinking. Neither are most of us equipped with his mind, skills, iron discipline and all-consuming, dominating drive to open up ways for those in his day and culture, to find and to know God, for themselves, through the all-sufficient atoning work of Christ. To see him in action is exciting and exhilarating, but are all his trails useful and safe for the generality of believers, even supposing they could follow him?

Gordon gives us many stimulating nuggets of Denney’s wisdom as he seeks to take the reader through Denney’s concerns about the centrality of the Atoning work of Christ at His Cross. He, also, brings out the passion of Denney’s life for his fellow Christians, particularly pastors; it was for them to be overwhelmed with the privilege of being brought into relationship with God through Jesus Christ, and for them to proclaim this saving truth to others:

q “Christ on his Cross is held up to us as the revelation of God to sinful men. What does it mean? It means (according to Paul) that the absolute reality, the final truth in the world, so far as God’s relation to sin is concerned, is this … He bears it, takes the weight of it, the pain and the shame and death of it upon Himself, and shows redeeming love to the sinful in so doing. Now what are we to do in face of such revelation of God? What is required of sinful men when faced with this as the last reality of the universe? Simply to let go … to abandon our lives to it without reserve, instantly and forever.”[22]

q “The only way to become perfect is to cherish the initial liberating impulse, to keep our being open to the whole stimulus of Christ, to grow and still to grow in the grace and the knowledge of our Lord and Saviour.”[23]

q “It is not open or unanswered questions that paralyse; it is ambiguous or evasive answers, or answers of which we can make no use, because we cannot make them our own. And it is not the acceptance of any theology or Christology, however penetrating or profound, which keeps us Christian; we remain loyal to our Lord and Saviour only because he has apprehended us, and his hand is strong.”

In conclusion, read Gordon – more – read Denney! – and be challenged, humbled and yet inspired by one who was prepared to think ‘outside of the box’. May many catch something of the passion for his Master’s Glory that motivated James Denney.

Soli Deo Gloria – To God Alone be the Glory.

[1] Gordon, James M: James Denney (1856-1917) – An Intellectual and Contextual Biography (Paternoster, London 2006).

[2] Letters of Principal James Denney to W Robertson Nicoll 1893-1917 (Hodder & Stoughton, London N/D [c1920]); Letters of Principal James Denney to his family and friends, Edited by James Moffatt (Hodder & Stoughton, London N/D [c1921]).

[3] Taylor, John Randolph: God loves Like That! – The Theology of James Denney (SCM Press Ltd, London 1962).

[4] Gordon, J M: op cit 213.

[5] Denney: Letter to W R Nicoll, Jan 19 1914, Letters of Principal James Denney to W Robertson Nicoll, (Hodder & Stoughton, London N/D c1920) 233.

[6] Gordon, J M: op cit 212.

[7] Cameron, Nigel M de S: ‘Believing Criticism’, Dictionary of Scottish Church History & Theology, edited by N M de S Cameron (T & T Clark, Edinburgh 1993) 69.

[8] Cameron: ibid 69.

[9] “Davidson had scarcely settled down to work in the New College before he began to feel a strange, unaccountable uneasiness. And when he got into touch with the men around him, walking and talking with them on the way to and from College … he found that the same feeling had taken possession of many of the best students in all the different years.” Strahan, James: Andrew Bruce Davidson (Hodder & Stoughton, London 1917) 56-7.

[10] Gordon, J M: op cit 73.

[11] Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland, 1891, 111-2: cited Gordon, J M: op cit 136-7.

[12] Gordon: ibid 137.

[13] Denney, James: Studies in Theology (Hodder & Stoughton, London 1894).

[14] Denney: ibid, Preface.

[15] Gordon, J M: op cit 146.

[16] Gordon: ibid, Note 35, 145.

[17] Darlow, T H: William Robertson Nicoll – Life and Letters (Hodder & Stoughton, London 1925)

[18] Nicoll, W R: Letter to James Denney, Aug 7 1894: cited Darlow, T H: ibid 341-2.

[19] Nicoll: Letter to Denney, ibid, cited Darlow ibid 341 & 2.

[20] Bebbington, D W: Evangelicalism in Modern Britain (Routledge, London 1989) 12-4.

[21] Dabney, Robert L: Discussions: Evangelical and Theological [Volume 1] (The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh 1890, reprint 1967) 438-9.

[22] Denney: ‘Preaching Christ’, Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels, cited Gordon: op cit 227.

[23] Denney: The Way Everlasting , cited Gordon: ibid 231.